This picture is from the Miami vs Kansas City game over the weekend.

Modern football helmets are made from polycarbonate.

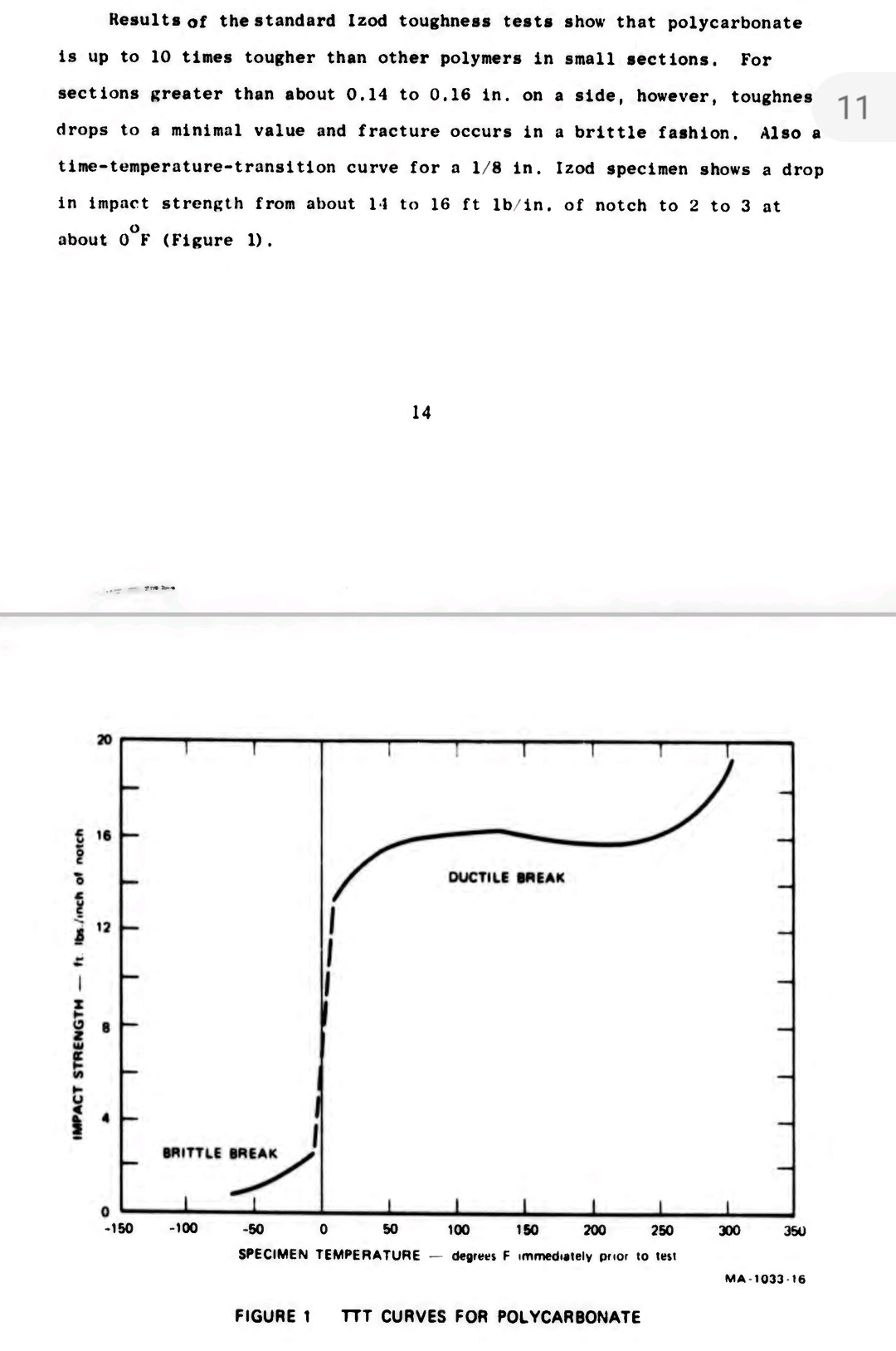

Polycarbonate, like all polymers, has a ductile to brittle transition temperature (DBTT). A temperature at which the material turns brittle like glass.

For polycarbonate, that occurs at roughly 0°F.

There is a test of fracture toughness, called an Izod impact test, in which a sample is struck with a hammer on a pivot, accelerated by gravity.

Izod data for polycarbonate is available.

You can see how much less force it takes to shatter polycarbonate at low temperature.

The temperature at kickoff was -4°F, one of the lowest in NFL history.

A tackle is a high impact event.

A high impact at low temperature causes brittle fracture.

Now consider this in cold weather when you use polymer magazines.

The Marines chose not to adopt PMags because of cold weather testing.

There are many documented examples of other polymer mags failing in the cold, cracking when dropped.

You may love your PMags, but if it gets cold where you live, consider having a selection of metal magazines for cold weather. Aluminum doesn’t ungerdo brittle transition at low temperatures.

Wow. I didn’t watch that game, but that must have been an unwelcome surprise.

I don’t quite understand the “small sections” bit. As worded it sounds like any shape that measures more than 0.15 inches or so in any direction is brittle. Helmets fit that description, so that can’t be right. Does it mean that it’s brittle if all dimensions are more than that — in other words, if you make the helmet too thick it becomes brittle?

You mentioned that metals don’t do this, but they can do something similar. I remember a neat exhibit at the science museum “Evoluon” (in Eindhoven, the Netherlands) in the 1970s. They had a liquid air making machine, and used that to show the effects of extreme cold.

One example involved putting a rubber ball into the liquid air, then dropping it onto a steel plate. It would shatter, just as you described.

Another example used a bell made of lead. At room temperature that just makes a muffled thump sound. But after sitting in liquid air for a bit, it would ring nicely like a normal bell. So the lead transitioned from ductile to hard/springy, though not brittle.

Some metals do. Crappy steel does, but most good steel won’t. Aluminum and austenitic (non-magnetic) stainless steel won’t. Mil-spec requires stability to -40°F.

I can tell you that any bolt you touch on any car that’s at a temperature below the freezing point of water, will break when you try to remove it. Ask me how I know.

I thought Pmags only started having issues at like -40? Which is below the temp that normal people will be using them. Or am I misremembering the temp? Your overall point is well taken though. I plow snow and when the temp goes negative, the amount of shit that breaks goes up exponentially.

Newer PMags are supposedly rated to -30°F, but there are older PMags and other polymer mags that are not rated to much below freezing.

The USMC banned use of all polymer magazines in 2012 due to guys using crap mags like Tapco and compatibility issues with gen 2 PMags.

In 2016 they made the M3 Pmag the standard and only authorized magazine for combat forces going forward after testing.

You can find pics online of USMC cold weather and winter training in Europe the last couple of years, and they are using Pmags.

The M3 was specifically designed to meet the Army cold weather specs by passing a drop test at -60 degrees.

It will have cracks, but still function.

It was the Army that was using the cold weather test to push their in house EPM mag, that was an aluminum mag with a knockoff Magpul follower, that in their own testing did worse than the Pmag.

And as of at least 2020, the M3 pmag is approved for the Army as well, and the EPMs designated for training use only.

PMags are -30°F. Mil-spec is -40°F. I can’t think of many polymers that go to -60°F.

https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.military.com/kitup/2017/10/magpul-disputes-army-claims-pmag-cold-weather-performance.html/amp

It’s the Military Times, so grain of salt, but thats my source for the -60 spec.

Hm. -60F isn’t quite good enough for winter on Antarctica.

i just put a sign up- “dear bad guys, do not assult me or my house during cold weather. if you do you or your estate will have to pay for fixing holes in my walls..owner does not come out in cold weather”…

Good point. I’ve also read that these stripper clips and loaders have similar issues in extreme cold–

https://www.impactguns.com/magazine-accessories/thermold-ar-15-10-round-zytel-mag-loader-w-3-stripper-clips-895389002338-mc-sc-m-16-ar15/

Pretty much any material will at some point undergo property changes as a function of temperature. The most obvious being melting/solidifying, maybe; but some materials can transition to a different molecular structure (or crystalline phase) without actually melting. If the new structure has a diferent density and the transition changes volume significantly, the results can be problematic.

.

Towards the low side, pretty much everything gets brittle if you get it cold enough, say, down to liquid helium temps.

Re crystal phase change: tin is notorious for that, resulting in “tin plague” which damaged many pipe organs in Europe back in the days when churches had no heat. Typical winter temperatures are well below the transition temperature (13 C).